The life of Carlos G. Vallés

I was born in Spain on 4.11.25. My father was an engineer, and his last work, a large dam in Ortigosa de Cameros now bears his name. When I visited the site, fifty years after his death, the engineer in charge told me: “If you see any large dam built fifty years ago in any part of the country, you’ll observe leakages, flaws and repairs. Here you can look down along the whole impressive spillway, and you’ll not see a single crack. Your father was known for the thoroughness of his work.” He died, when I was ten, of “Vincents’ angina”, a throat disease which is now easily cured with antibiotics, but these did not exist then. Though I was so young when he died, I’ve always felt he is the person that has exerted the greatest influence on me, because of his stress on excellence, his honesty and his trust in me. When I was eight, I went down with pneumonia, which – again because of the lack of antibiotics – was deemed close to mortal in a child. I spent three months in bed. When I recovered and, still weak, went back to school, I heard my mother ask my father: “What can Carlos do now? He has lost three school months, and the examinations are coming. He won’t be able to sit for them.” My father answered her: “Don’t worry about Carlos. I can get him ready for the exams in fifteen days.” Those words shaped me. My father trusted me. I would never let him down.

Six months after my father’s death, civil war broke out in Spain. The country was split into two, our home remaining on one side, and my mother, my brother and I, with only the clothes we had on, on the other. We lost all we had. My mother took refuge with a sister of hers in a city where the Jesuits had just opened a school, and my brother and I got scholarships to study in the school and stay at the boarding.

From the Jesuit school to the Jesuit noviciate was only a step for me. I was fifteen. In my book “The Art of Choosing” I have openly reflected on this turning point of my life. It was the first spiritual detachment, that is, leaving the family for Christ, which constituted the religious vocation. Given my character and my inherited thoroughness just now mentioned, this first detachment was soon followed by the next one, that is, leaving the country for Christ, or missionary vocation. I asked to be sent to the East. I was informed that our order planned to start a new St. Xavier’s College in the city of Ahmedabad, to follow the glorious tradition of the Xavier’s Colleges of Mumbai, Calcutta and Madras, and there I went in the fullness of my youth. My father had taught me never to do things by halves.

On arrival in India I felt quite at home from the start. My Hindu friends had a ready explanation for it. According to them, in my previous incarnation I had been an Indian, hence the home feeling. I went to the prestigious Madras University for my mathematics degree through English… knowing neither English nor mathematics. I chose the “honours course” in which a single public final exam on all the subjects of all the B.A. and M.A. years decided our fate… and in case of failure the exam could not be repeated! I graduated with first class on 1953.

By then I had realised that English, however much extended in the academic field, was a foreign language in India. It was enough to teach mathematics, but not to reach the hearts. The heart is reached through the mother tongue. In my region that was Gujarati, which also was Mahatma Gandhi’s mother tongue. I studied it during the “language year” prescribed for all Jesuit seminarians, but I realised that one year was not enough. That year chief minister Morarji Desai had decided that no more visas would be granted to foreign missionaries, and that foreign seminarians now in India would only be allowed to complete their studies in India and would then have to return to their own countries. In that situation, all my companions went to Pune to do their theology with a view to the priesthood, without further interest in a language they were not going to use. I remained for one more year to perfect my Gujarati in spite of all odds. I went to Vidyanagar University, stayed in the hostel surrounded by Hindu students, shy and tall as I was in my white cassock and faulty speech, unmindful of the uncertain future. If I knew Gujarati, I had to know it well. My father had taught me not to do things by halves. That year changed my life.

Next came four years of theological studies in Pune, and those four years I began every study day with two hours of Gujarati writing… to be dispatched to the waste-paper basket as I wrote only to exercise my future pen. Then Holy Scripture, Christology, “Indology”, Moral Theology. Four dense years with their summit in the priesthood I received on 24.4.58 in the presence of my mother who then came for the first time to India. She had written to me some time before: “I do not understand how the whole of India is not yet Christian… given the sacrifices so many mothers of missionaries have offered for her.” Our meeting was truly blessed.

I started my mathematics teaching in Ahmedabad the year Gujarat separated from Mumbai and became a new state (1960). Thus I grew with it from the start. I gave myself body and soul to my teaching. Before me in each lecture hall were a hundred boys and girls, the cream of the land, eager to learn and quick to grasp the most abstract theorem before I could state it. “Modern Math”, as it was then called, was beginning to be taught in India with its baggage of sets, groups, rings, fields, vector spaces, matrix algebra…, and I introduced it in the Gujarat University, coining, as I went along, new terms for new concepts. “Set” was” “gan”, as Ganesh is the god (ish) of the clan (gan); and “ring”, of course, was fittingly and tellingly “mandala”. The terms have stuck. However, when I proposed to call a “one-one relation” a “Sati-sambandh”, and a “one-many relation” a “Draupadi-sambandh”, some eyebrows were raised, and the terms were rejected, much to the dismay of lovers of Sanskrit lore.

I helped start the first mathematical review in an Indian language, “Suganitam”, to every issue of which I regularly contributed an article on current research; co-authored the volume on mathematics in the official Gujarati encyclopaedia “Gnanganga”, and conducted seminars and summer courses for mathematics teachers all over Gujarat. I represented India in world mathematical congresses in Moscow, Exeter and Nice.

In 1960 I published a little book in Gujarati, addressed to the modern college student in India, with the cherished idea of launching a person-to-person dialogue with my students beyond the classroom. The publisher I first approached with my manuscript threw it literally to the floor and said deridingly, “Who will ever read this book?” His attitude, however painful to me, was not devoid of reason, as I was a totally unknown author, and, on top of it, I had chosen for my book the unfortunate name of “Sadachar”, which was not particularly appealing to anybody, let alone young readers. My mother sent me some money from Spain, and I became my own publisher. The book has to this day seen twenty editions in three languages… without changing its title!

Shortly after that first book, the editor of the family monthly “Kumar” asked me to write for his magazine. Kumar’s prestige was so great that I thought the invitation was merely a polite pleasantry, and wrote nothing. I continued with my teaching and my mathematics. Five years later the same editor and I happened to meet at a party, and he drew close to me and told me gently, “Do you remember my invitation of five years ago? It is still standing.” This time I believed him and sent him an article. I wrote every month, and at the end of the year I was elected for the “Kumar Price” for the best contribution to the best magazine. Since then I combined my mathematical and my literary activities.

Still, the turning point came a little later with my entry into the daily press. The editor of the main Gujarati daily at the time, the Gujarat Samachar, called me one day to his office. He went straight to the point and said, “I want you to write an article each week in the Sunday supplement of my paper.” I countered, dumbfounded, “And what shall I write about?” He told me curtly, “The same stuff you write in Kumar.” The deal that was to change my personal landscape from then on was sealed. There was no television in those days, and the main family entertainment every Sunday morning in every home was the rich and varied supplement of the Sunday paper. Together with it I entered those homes with a series I called, “To the New Generation” (with the secret hope that the old generation would read it first!). Sunday by Sunday that series built lasting ties between me and thousands of readers all over Gujarat.

The articles were soon collected into books. My writing increased. My Hindu colleagues in the mathematics department, in a generous and spontaneous gesture I’m to this day deeply grateful for, undertook to take away from me the routine work of tutorials and examinations so that I could be more free for my writings. I also wrote together with them a whole series of mathematical textbooks in Gujarati for all the subjects in the new syllabus, which soon became as popular for its clarity as hated for its difficulty. A whole generation of science students knows me more by those textbooks than by my literary works.

These literary books on youth, family, society, religion, psychology, morals…, went also increasing, and today I believe they are more than seventy, though I’ve never counted them. Last year my publisher in Gurjar Granthratna Karyalaya brought out a five-volume set with all that seems worth keeping for posterity in my whole work. Usually such editions are made after an author’s death, but I have been fortunate to see it alive. It has given me a great satisfaction.

The Gujarat government gives every year several literary prizes to the best book in different categories: novel, history, biography, poetry, essay. The essay prize came to me in five consecutive years, till the government brought out a law by which no author could get a prize more than five times. More important for me was the “Ranjtram Gold Medal” granted to me in 1978, as this is the highest cultural award in Gujarat, for the first time awarded to a foreigner.

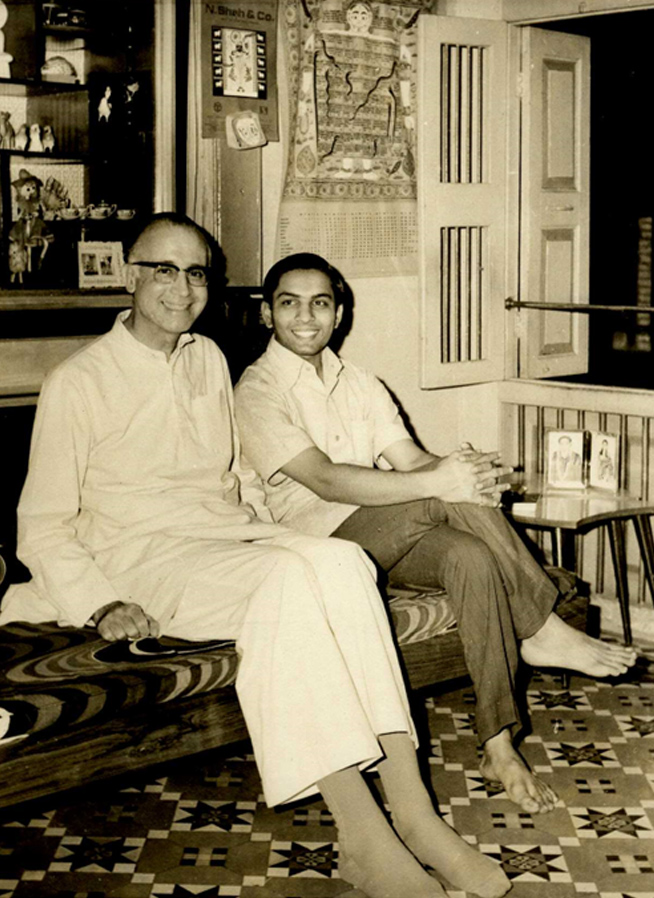

All this recognition brought me closer and closer to my readers, but even so I felt a great distance between my isolated life in the Jesuit staff quarters of our college and the humble residences of my readers in the remote areas of the old city. I then thought of going to live with them. I took a sling bag with bare essentials, got on my cycle, and went to beg for hospitality from house to house in the traditional area within the city walls. Indian hospitality opened doors to me, in homes and families, and so I lived the whole day with them, sharing their two daily vegetarian meals, their floor space on a mat at night, and their family life in all its richness, blessings and problems for a few days till I knocked at the door of another family in a continuous pilgrimage. I cycled daily to and from the college for my classes, but for the rest I lived fully as a member of the family I lodged with for the time. I spent ten years in that happy way. Perhaps that is possible only in India.

Those domestic wanderings brought me to Hindu, Jain, Parsi, Muslim, Christian homes, thus giving me the chance to know at close quarters and literally from the inside different mentalities, attitudes to life, beliefs and traditions. This experience received its recognition in the two official citations I treasure best. In 1995 I received in New Delhi the “Acharya Kakasaheb Kalelkar Award for Universal Harmony”, and in 1997 the “Ramakrishna Jaidalal Harmony Award” for my lifework in favour of mutual understanding, appreciation and unity between people of different languages, cultures and religions. The word “harmony” is in both citations. I would like it to be the summary of my life.

All those years I felt so identified with my language and culture in Gujarat, that I stoutly refused to write and publish anything in English. At long last I yielded to the request of the “Gujarat Sahitya Prakash” publisher, and I wrote my first book in English, “Living Together”. The book made well, and had to be followed by others. No only that, but it brought me the request of the “Sal Terrae” publisher in Spain to put the book into Spanish, and that opened up a new front for my writings. Spanish language means not only Spain, but twenty countries in Latin America where Spanish is mother tongue to millions of people. My books began reaching them too, and brought back to me invitations to visit those countries and lecture to their peoples.

Happily, by then I had officially retired from my mathematics chair, and was free to travel. The thought of leaving India had never crossed my mind, but I believe in being led by circumstances, and these shaped new and unexpected paths for me in my life. My beloved mother, when she reached ninety, asked for my company in her old age, and I was happy to obtain permission to do so. This brought me to spend from then on most of my time by her side in Madrid, Spain, while I remained devoted to my writing in three languages and my travelling to many places. My mother lived till she was a-hundred-and-one, and to accompany her in her last years has been one the things that has given me the greatest satisfaction and fulfilment in my life.

A new dimension was still added to my life when, only two years ago, I shook down laziness, bestirred myself, bought myself a computer and got into the electronic world. In October 1999 I opened this Web site in Spanish, and now I’ve started its parallel in English. This is, without any doubt, the field of the future, and I feel a new joy as I gingerly, humbly and expectantly begin to step into it. I have now settled in Spain, and I strive to bring to fruition the synthesis of my Spanish roots, my identification with India, and my own “discovery” of Latin America. In the Indian languages we have the expression “to live two lives in one”. ¿Could it be three for me?